When I introduced Foundations of Business Penmanship I described the series as “Lessons to Supplement Self-Study.” In addition to writing the actual lessons, I thought it would be helpful to devote some space on this blog to the “self-study” portion, answering one question in particular:

What does a successful self-study system for business penmanship look like, and how can we tailor such a system to suit our individual goals and learning styles, so as to ultimately find the best path for improvement?

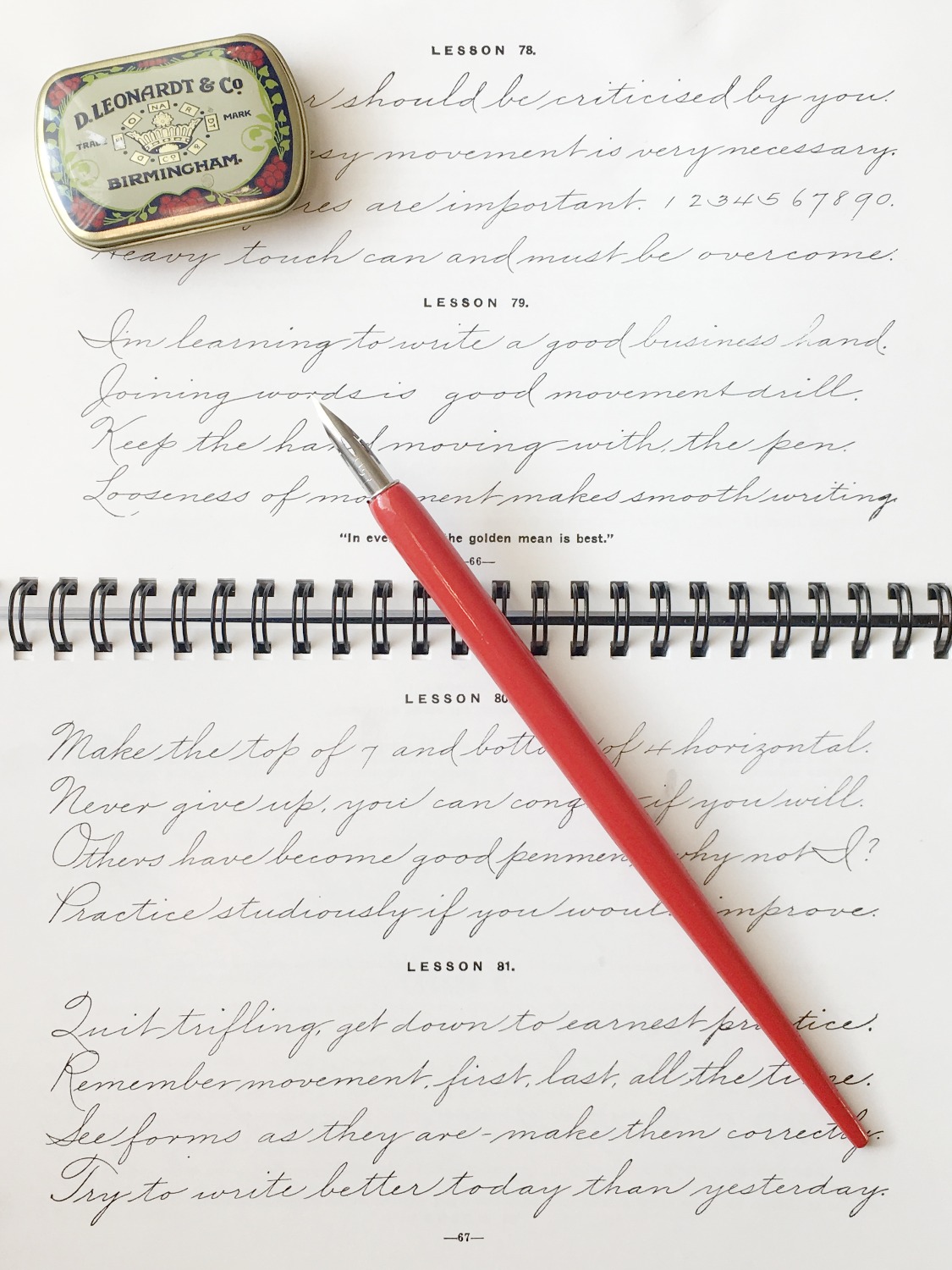

One of the most important initial steps in creating your own learning system is to establish a collection of resources that will be your core reference materials, around which you will structure your practice. It so happens in the realm business penmanship, (unlike with so many other historical scripts) that the primary source material available to us comprises not only fine written exemplars, but a wealth of thorough, tried-and-tested instruction on the methods and techniques of writing. And while no single book can teach us everything we need to know, it can at least provide us with a significant head-start.

Take a trip to the Library of American Penmanship

(Ok, don’t you just wish it was a real place—dusty shelves, rolling ladders, quiet corners with writing desks where you can work through a few pages of Mills of Zaner?)

While that place may be just a fantasy, in this age of the internet, it is incredibly easy for us to build our own digital library, thanks to the contributions of IAMPETH, university collections, and repositories like Google Books and archive.org.

Browsing the business penmanship section of our library, we would come across a lot of material—copybooks, method books, periodicals, pamphlets, writings on the theory and philosophy of penmanship, manuals for teachers, and much more. It can be a bit overwhelming and difficult to know where to look first. To simplify this process, I have provided a list of some of the more well known items on the shelf, as well as a bit of commentary on each one.

F.W. Tamblyn’s Home Instructor in Penmanship (first edition, 1911)

F.W. Tamblyn

This is a thorough course in business penmanship and a superb all-around resource to use as part of a daily practice routine. I highly recommend it.

I especially like Tamblyn’s detailed illustrations showing the particulars of position, pen hold, and muscular movement. I also find his copies (handwritten exemplars) to be some of the best reference material anywhere, as they are true to his “movement-first” approach. In other words, they are, as he says, “photoengraved from actual free hand, rapid writing” and therefore demonstrate a level of accuracy and consistency that can be realistically achieved using only the techniques described in the book.

A few notes:

1) While Tamblyn’s introductory lessons include some excellent exercises for developing movement, I don’t find that he is as creative in his approach to applying drills directly to letterforms as some other authors—Mary Champion or H.P. Behrensmeyer, for example (see below.)

2) This is the only book in this list that is still in print and therefore not in the public domain. The 8th edition, published by Ziller of Kansas City, can be purchased at Paper and Ink Arts and John Neal Bookseller.

The Champion Method of Practical Business Writing (1921)

Mary L. Champion

I discovered this book fairly late into my learning process but it quickly became one of my favorites. I love Champion’s creative and sensible use of drills to tackle difficult parts of certain letterforms. The Champion Method is similar in scope to Tamblyn’s Home Instructor in that it is designed to be a “complete course.” I would definitely recommend using the material in this book for regular practice.

One thing to note: the first few lessons include what Champion calls “our first attempt at a sentence.” She recommends spending “some time” on it “even if it is difficult.” I might encourage you to not spend too much time on sentences in the beginning, however, and rather focus your efforts on one movement, one gesture, one letterform at a time. Your practice will be more effective because of it. Champion’s next lessons incorporate longer words and phrases in a much more logical way, using the forms that you already will have practiced. You can (and should!) always come back to that first sentence later to see how you have improved!

The Palmer Method of Business Writing (first edition, 1901)

A.N. Palmer

(Also see, Palmer’s Guide to Business Writing (1894), an earlier publication with a slightly different approach—well worth the read.)

Though “The Palmer Method” is often used as a generic term for any style of mid-twentieth century schoolroom cursive, it really was a method (a highly influential one) for teaching children a style and technique that was already in common use at that time in the business world. Palmer was very good at marketing himself and his curriculum, and his name has since stuck!

Because of Palmer’s prodigious influence, his book has come to be regarded as the handwriting improvement bible, at least for those interested in adopting a classic style. But while The Palmer Method is a very useful reference to have, it’s actually not my preferred resource for self-study.

Palmer’s book was designed specifically to be used in a classroom by teachers trained in his method. Despite the extensive introductory material and commentary throughout, I don’t find his progression through the initial stages of movement training to be logically ordered nor particularly effective in the absence of a live instructor and a standardized school penmanship curriculum.

To be clear, there is much to be gained from using this book—studying Palmer’s copies would be worthwhile alone—but as a comprehensive course in penmanship it doesn’t stand on its own as well as Tamblyn’s Home Instructor or The Champion Method. If you desire to learn the Palmer Method literally “by the book,” you will be most successful using it in conjunction with other material.

The Arm Movement Method of Rapid Writing (1904)

C.P. Zaner

Much of what I have said about Tamblyn’s Home Instructor and The Champion Method applies to this superb book as well. It is a comprehensive series of lessons with a wealth of written instruction and detailed introductory material. It could easily be used as a primary method book for daily practice. Indeed, after examining Zaner’s lessons in more depth for this review, I want to utilize this book more often in my own routine.

Something I find interesting about Zaner’s approach is how he often links the capital and lowercase versions of a certain letter within the same lesson, when the two forms are closely related and use a similar movement, such as in M, N, P, U, V etc. I think this is a great way to keep your movement consistent and continuous between large and small letters, which is key to the easy and rapid execution that Zaner advocates.

Modern Business Penmanship (1903)

E.C. Mills

If you are like me, and regard E.C. Mills as one of the finest penmen of his age, then Modern Business Penmanship is a must-have resource in your library. That said, though I refer to this book continually, I would not recommend it as a primary method book for a complete beginner in business penmanship. For one thing, the actual written instruction, especially on the technical fundamentals is quite limited in comparison to what Tamblyn or Zaner, for example, provide in their books (though I am sure that this is due only to space limitations.) In many ways, it is more of a handbook, though an excellent one.

I particularly like the emphasis Mills places on reducing the size of the push-pull and oval exercises—a crucial step for learning to constrain (and retain) the natural power of the arm movement mechanism within the space of the small letters:

The copies themselves warrant their own caveat. Mills’ style of business penmanship is beautiful, refined, and worthy of imitation, but I would caution anyone not to become preoccupied too early on with adopting every last detail of Mill’s forms, for two reasons:

1) The copies are very near perfect, and while they still, as Mills says, “show the skill of the penman and not that of the engraver,” the writing doesn’t necessarily represent a true business hand in the way that the exemplars of the four above authors do. Mills’ exemplars were likely written very carefully—not rapidly—and perhaps (though I can’t say for sure) at a larger size to ensure greater accuracy before being reduced for printing. In short, it is not casual, everyday penmanship, at least not for those of us who are not E.C. Mills!

2) The tall, angular style of Mills’ forms don’t lend themselves naturally to the kind of free movement technique that he and other authors recommend, especially for a beginner. I find in my own writing that the most natural forms that develop out of a strong and continuous arm movement, without other manipulations, are more rounded and far less nuanced than the letters in Modern Business Penmanship.

Lessons in Practical Penmanship (1917)

H.P. Behrensmeyer

This is an excellent book, with one of the more intuitive sequences of introductory drills I have seen. Behrensemeyer distills his technique into a few basic exercises, then logically develops them into more complex gestures, then letterforms. In particular, I like the way he illustrates the development of the lowercase m.

While this is representative of the “official” movement-first approach of all business penmanship tutors of this time, Behrensmeyer’s sequence is quite thorough and includes important details that are sometimes overlooked in other books and lessons.

The author also shares some unique drills for specific letterforms that are a good inspiration for coming up with your own. Be sure to spend some time with this book!

Finally, be aware, that like most authors of these lesson books, Behrensmeyer is limited by space. Take his copies as a starting point and a guide for how to practice, but don’t limit yourself to them. As he says, “Many students are too dependent upon the text, and their advancement is slow because they do not do enough original thinking in connection with their practice.”

A Complete Compendium of Plain Practical Penmanship (1901)

Lloyd M. Kelchner

I like to think of this book as a guide to practice rather than a comprehensive course. It really is, as the title says, a “compendium”—the individual lesson plates are not accompanied by any written commentary or instruction. Don’t ignore it for that reason, though—with a little creative thinking you can get a lot of use out this book.

A few things I like are the excellent introductory movement exercises and the logical organization of the lessons, based on whether letters are formed from the direct (counter-clockwise) or indirect (clockwise) oval. This structure makes Kelchner’s lessons quite intuitive despite the lack of written direction.

Be aware that Kelchner does not show drills or developments for each letter, but rather often shows a few warmup gestures at the top of the page that use the essential movement behind the group of letters below. As usual, don’t just “copy the copies.” Modify the warmups at the top of the page into proper drills for each letterform.

We’ve only just scratched the surface here, but I hope these notes will help you start collecting, combining, and utilizing these resources to their fullest potential.